Why everyone is a little bit culty (including you and me)

I have been listening to the Podcast “A Little Bit Culty” for years, have watched just about every cult documentary on Netflix, Max, and Amazon, and have examined every group I’ve ever been associated with wondering whether I was in a cult or not. As someone who has held various leadership roles throughout my adult life, this scrutiny has become an essential practice—a way to continually examine the dynamics of influence and power in my own work. Every leader, no matter how well-intentioned, risks creating unhealthy dynamics if they’re not actively working to understand and prevent them. So I keep learning, keep examining, and keep diving into these spaces as reference points for what to avoid.

My fascination with culty dynamics also stems from my interest in the deeper aspects of human psychology and my own experience with emerging from deeply ingrained belief structures that most people find normal. Much of my life has been spent as a proverbial outsider, but this has been precisely because I have made myself an outsider by constantly upending my belief structures. Though I am not a survivor of cultic abuse, nor was I raised in what most people would consider a cult, I’ve come to see cults not as rare birds to be spotted and analyzed, but as projections of ourselves and our needs. Having essentially pushed myself into a land of near total alienation by challenging all of my fundamental beliefs, I feel I have some wisdom to share in this realm. But, of course, take it all with a grain of salt.

Let me start by saying something controversial: Everyone on this Earth is in a cult—Yes, I mean you. And, I mean me. And, I mean everyone, everywhere.

The cult we all belong to is hiding in plain sight: Culture itself. I once heard someone delineate the difference between a cult and culture as simply the number of people involved. And, despite my inability to attribute this definition properly (thank you to whoever said this), it is probably the truest statement I’ve heard, and one that requires deep inquiry.

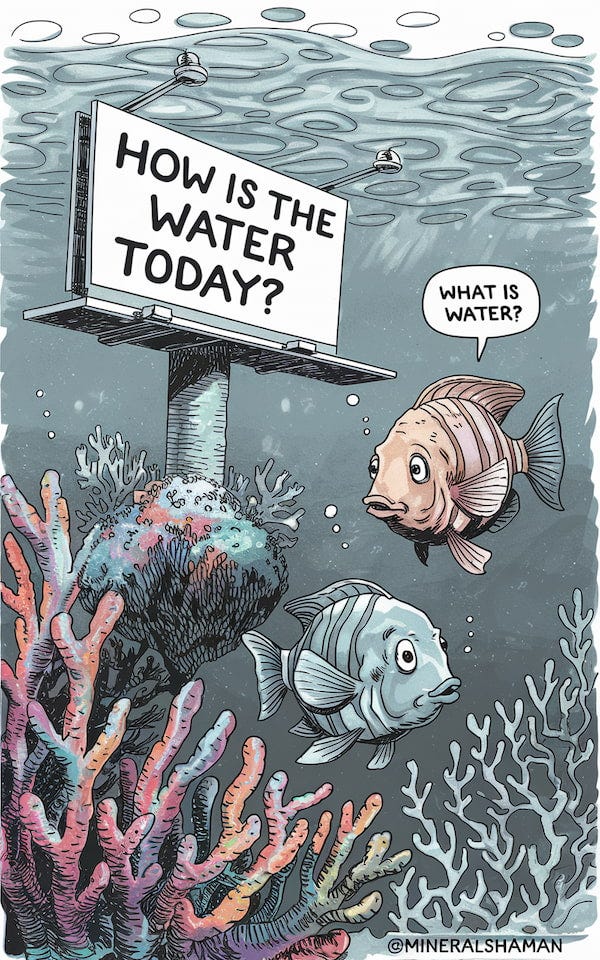

To understand this tension between culture and cult, we need to introduce another word into the conversation: paradigm. Culture itself is built upon layers of paradigms—shared frameworks that shape how we interpret and interact with reality. There is an inherent tension at play in the human psyche around our beliefs, paradigms, and ideas. They are not the same thing, but they swim in the same waters, each influencing and reinforcing the others. While beliefs can be changed relatively easily and cultural practices might evolve over time, a paradigm is more than just a theory or methodology—it’s an entire framework for understanding reality, complete with its own assumptions, language, and ways of determining what constitutes valid evidence. When we speak of breaking free from cultural conditioning or cult-like thinking, what we’re really talking about is the challenging work of recognizing and sometimes shifting our fundamental paradigms.

What fascinates me most is how fiercely we protect these paradigms. I began to understand this protective mechanism more deeply through my work with Internal Family Systems (IFS), a therapeutic framework I explored with professional guidance, I’ve come to understand how different parts of our psyche work to protect us from emotional harm and maintain psychological stability. In IFS, these “protector parts” develop early in life to shield us from overwhelming experiences. One particular protector I’ve identified in myself—what I call the Paradigm Protector—emerges specifically to guard my fundamental belief systems.

This Paradigm Protector comes in whenever a fundamental framework is challenged, and it can manifest in fascinating ways. One tell-tale sign I’ve noticed in myself is when my logical mind kicks into overdrive. While I used to pride myself on being “very logical,” I’ve come to recognize that my tendency to deploy rigorous logic and reason often signals that a protector part is at work. When I’m not being ruled by a protector, I actually settle into a less rational mindset (more heart-centered in orientation).

Interestingly, for some people, their protector manifests in the opposite direction—they retreat into magical thinking or supernatural explanations when their core beliefs are challenged. My pattern of intensified logic seems particularly common among those who pride themselves on their analytical thinking (a knowing wink to my fellow lawyers, academics, and analytical types out there).

I came to understand the power of this Paradigm Protector most vividly when I first encountered challenges to what I considered an unquestionable truth: the paradigm of contagious illness. Almost everyone agrees that people pass illnesses to each other—indeed, this paradigm is so well-established that most people would say it’s established fact. When I first heard this discussion challenged years ago, I had an instant desire to simply reject any challenge to the notion. My mind went into overdrive: “Of course there are contagious illnesses, there are viruses, and a host of other things we pass to each other.” Satisfied that there was nothing to see there, I simply blocked out the noise, found a few parts of the counterargument to look at, and then dismissed the notion as pure nonsense.

What made this particularly interesting was how cognitive dissonance manifested in my own experience. Even when confronted with personal experiences that didn’t fit neatly into established frameworks, my Paradigm Protector would work overtime to maintain the status quo, finding creative ways to explain away inconsistencies. This process of questioning and eventually shifting my perspective didn’t happen overnight—it unfolded gradually, each stage bringing its own unique blend of intellectual curiosity and emotional turbulence. I discovered that stepping outside of an established paradigm isn’t merely an academic exercise; it’s a deeply personal journey that can trigger feelings of isolation and even existential uncertainty.

As I navigated this territory, I became increasingly attuned to the emotional undertones of my resistance. When I notice strong emotions arising as a belief is challenged, I’ve learned to recognize it as a signal that I’m encountering something deeper than simple disagreement—I’m likely brushing up against a core paradigm. Through my work with Internal Family Systems (IFS), I’ve come to understand these emotional responses as signs that a protector part is actively working to maintain psychological equilibrium. The real challenge lies in recognizing this protection for what it truly is: a well-intentioned but sometimes constraining force in our psychological landscape.

IFS has been instrumental in helping me navigate these waters, though I should note that it’s a sophisticated therapeutic framework best explored with professional guidance. These protector parts aren’t adversaries to be overcome—they’re aspects of ourselves that developed for important reasons. Learning to work with them rather than against them requires patience, skill, and often the support of a trained therapist. This approach has helped me maintain stability while still remaining open to paradigm shifts, allowing for growth without compromising psychological safety.

Understanding how my own Paradigm Protector operates leads me to an important caution I often share: “Swallow the red pills slowly, my friends.” There’s no need to completely unsettle our reality all at once. While some of us might be drawn to radical paradigm shifts and feel energized by exploring uncertainty, others might choose to maintain their existing frameworks, and that’s perfectly valid. The goal isn’t to demolish all paradigms but to develop a healthier relationship with them.

As numerous wise ones have observed, “a great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices.” This insight helps explain why paradigm shifts can be so profoundly unsettling—they require us to question not just what we think, but how we think.

I witnessed this distinction play out clearly in the alternative health space, where I have observed many influential voices constantly changing what they think without changing how they think. They encounter new ideas but view them through their old paradigmatic lenses, often misunderstanding and ultimately rejecting them because they haven’t shifted their fundamental way of thinking. It’s like trying to understand quantum physics using Newtonian physics—the framework itself needs to change for true understanding to emerge.

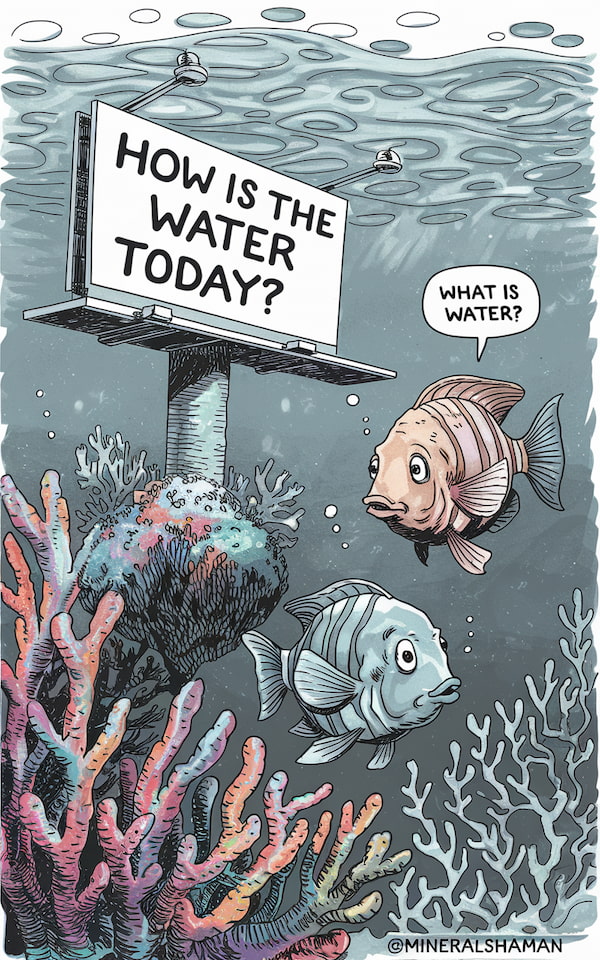

This blindness to our own frameworks of thinking is perhaps the most challenging aspect of paradigm shifts. David Foster Wallace captured this invisibility beautifully in his “This Is Water” speech when he observed that “the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” We swim in our paradigms like fish swim in water, rarely noticing the medium that shapes our every movement and perception. This is why the term “brainwashing” is both accurate and misleading—it suggests a forceful rewriting of someone’s paradigm, but the truth is that once a new paradigm is installed, it becomes our new water. Without developing epistemic humility—which isn’t natural or easy to cultivate—we can’t see that we’ve been “brainwashed.” Yes, that means all of us are “brainwashed,” in a way. This invisible conditioning becomes most apparent when we observe how even those who study belief systems can be blind to their own paradigmatic assumptions.

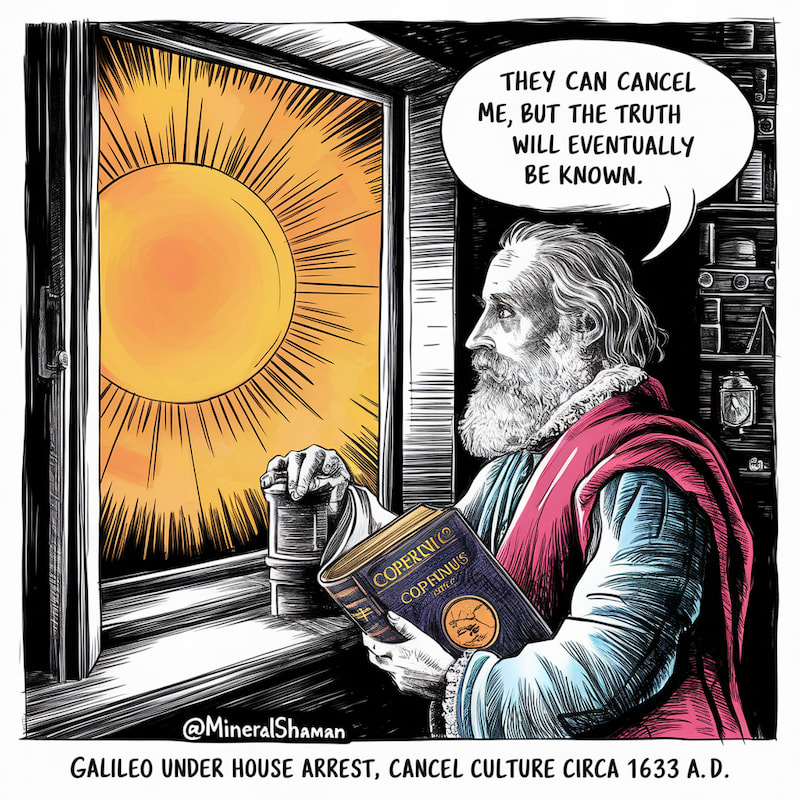

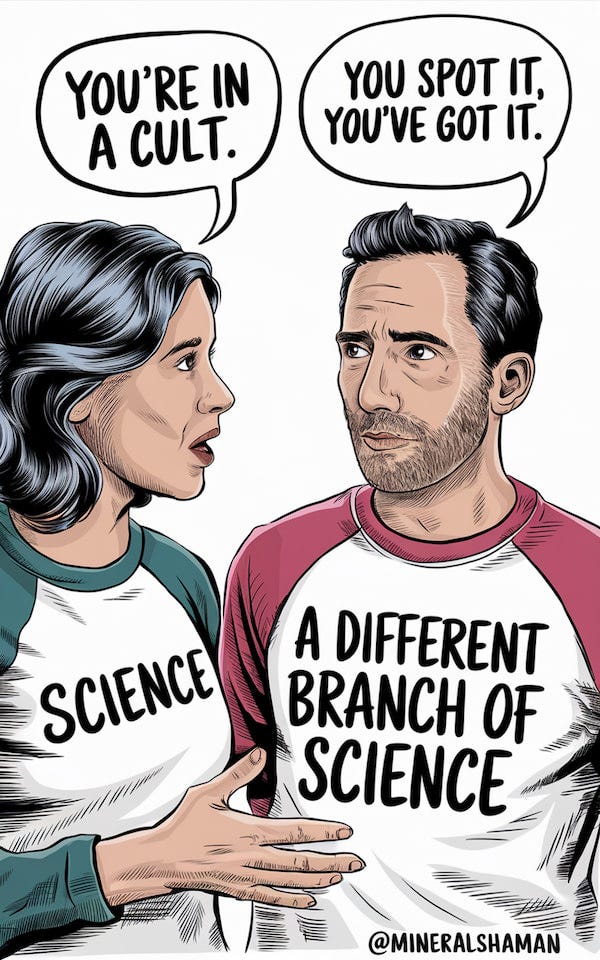

This dynamic plays out fascinatingly in the very podcast that initially sparked my exploration of these ideas. In “A Little Bit Culty,” the hosts skillfully identify cult tactics like “word salad” (meaningless ideas hidden in seemingly profound prose), “thought terminating cliches” (statements that end debates and make topics beyond logical argument), and various logical fallacies. Yet, knowingly or not, they sometimes employ these same tactics when discussing beliefs that challenge their own paradigms. For instance, I’ve heard episodes where they or their guests paint people who question vaccination or the predominant paradigm of germ theory as culty, misguided, or uninformed. When I hear these moments, I think, “Ah ha, there’s the Paradigm Protector kicking in.” What they label as unscientific or illogical in others, they’re unwilling to examine in their own paradigm.

I’ve noticed this pattern playing out in various podcasts, including those of thoughtful friends who examine alternative health paradigms. While their critiques often raise valid concerns, I notice how even in careful analysis, we can unconsciously employ the very tactics we critique in others: using guilt by association, focusing on the character of belief systems’ founders rather than the ideas themselves, and sometimes inadvertently mischaracterizing core concepts in ways that make them easier to dismiss. What strikes me most in these discussions is hearing the deep emotional investment in people’s voices—that particular tone that emerges when deeply held beliefs are challenged. I recognize it immediately because I’ve heard it in my own voice so many times before. These moments remind me that we’re all susceptible to our Paradigm Protectors, even—or especially—when we believe we’re being purely rational.

Recognizing this pattern in myself led me to develop a rather unconventional practice: I began actively seeking out and deeply exploring precisely those paradigms that trigger my strongest knee-jerk reactions. Recent deep dives have included the world of Sovereign Citizens who believe we can live free of taxes and government control, Global Skeptics (aka Flat Earthers), and many more. My loved ones sometimes find these explorations concerning. When I went into the depths of the Flat Earth world, some around me watched with trepidation. I kept trying to explain that my intent wasn’t to become a Flat Earther but to understand everything I could about the paradigm—yet this was naturally unsettling for those close to me.

For me, these explorations have been invaluable exercises in epistemic humility. They’ve helped me practice admitting how much we really don’t know and emerge feeling freer of dogma from all sides by fully exploring every conceivable avenue. You might be wondering if I ended up a Flat Earther. The answer is no, but I gained a deep understanding of why they hold these beliefs and the frameworks they use to interpret evidence. What’s particularly interesting is how this exploration revealed my own reflexive responses to challenging ideas. I noticed how quick most of us are to dismiss unfamiliar paradigms through logical fallacies rather than seeking to understand their underlying reasoning. Indeed, I’ve found many of these researchers to be incredibly thoughtful people who are simply evaluating the same evidence through different interpretive frameworks and arriving at different conclusions.

Some might worry that this approach to holding beliefs lightly leaves us vulnerable to manipulation or cult influence. After all, isn’t our Paradigm Protector there for a reason? This concern gets to the heart of a fascinating paradox: the very mechanisms we develop to protect ourselves from manipulation can sometimes make us more vulnerable to it. True epistemic humility—the kind that comes from deeply examining our own beliefs and understanding how paradigms work—actually provides better protection than rigid certainty ever could.

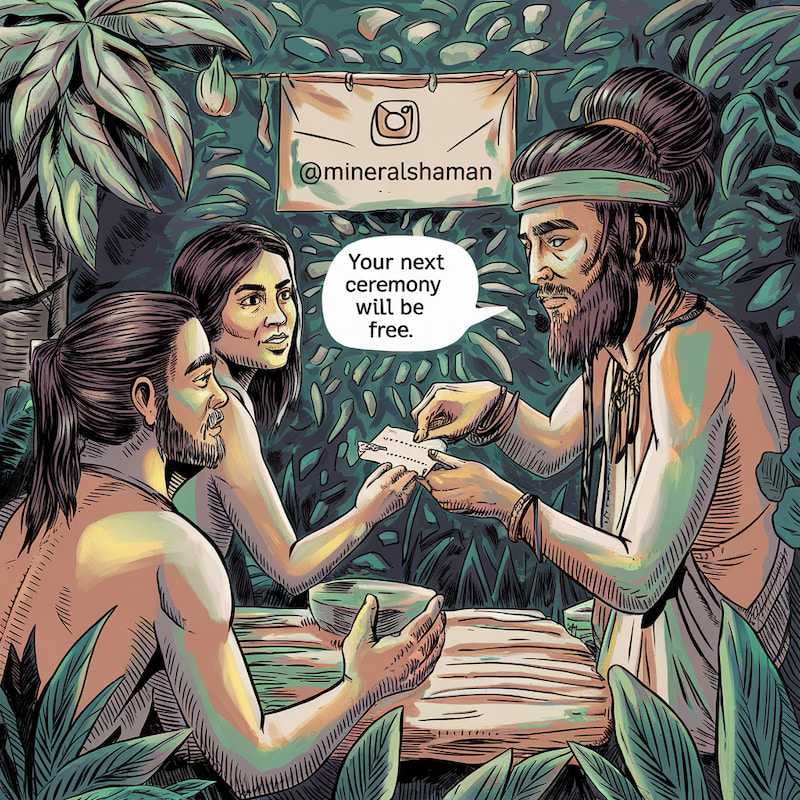

I’ve witnessed this protective power of epistemic humility firsthand. During my time with indigenous teachers in the Amazon, I observed how many Western seekers became totally immersed in the paradigm, some even adopting Shipibo names as their own. While I deeply respected the teachings, my practice of epistemic humility allowed me to metabolize the wisdom while maintaining discernment. Similar dynamics played out in various plant medicine circles, alternative health communities, and yoga lineages—spaces often labeled as cults due to their counter-cultural views or charismatic leadership.

This brings us to a crucial distinction: we must absolutely honor and listen to the voices of cult survivors while being mindful of how quickly our culture defaults to labeling any unconventional group or practice as cultish. The documented abuse within organizations like the Kundalini Yoga community under Yogi Bhajan demonstrates why we must take cult accusations seriously. Yet the tendency to broadly apply the cult label to any challenging paradigm can become its own form of thought-terminating cliché—a way to dismiss ideas without engaging with their substance.

What I’ve discovered through these explorations is that true intellectual freedom doesn’t come from finding the “right” beliefs or maintaining perfect vigilance against “wrong” ones. Instead, it emerges from developing a more sophisticated relationship with belief itself. When we understand how beliefs form, how they can calcify, and how they can be challenged, we develop a form of protection far more nuanced than mere rejection or acceptance could provide.

This brings us full circle to where we began: while the line between cult and culture may indeed be largely a matter of numbers, our ability to navigate both depends not on the strength of our convictions, but on our willingness to question them. In embracing epistemic humility, we don’t become more vulnerable—we become more discerning. We learn to swim consciously in whatever waters we find ourselves in, always aware that there might be other waters we haven’t yet explored.