PART 1 – THE VIRAL ILLUSION: HOW HUMAN PSYCHOLOGY AND FAILED SCIENCE CREATED MODERN VIROLOGY

Introduction

In January 2020, a team of Chinese scientists announced they had discovered a new virus. Within weeks, their computer-generated genome sequence became the foundation for worldwide PCR testing, launching an unprecedented restructuring of human society. Schools closed, businesses shuttered, and billions of people altered their behavior based on the belief that an invisible particle was spreading through the air, causing disease and death.

This dramatic global response rested on a remarkable assumption: that virologists had proven the existence of a new pathogen. Yet if we examine what actually happened in those early weeks of 2020, we find something surprising. No scientist had physically isolated or purified any viral particle. No one had demonstrated that this supposed virus could cause disease. Instead, they had created a theoretical genome using computer software, detecting genetic fragments whose origin remained unknown.

How could such momentous decisions be made based on such limited evidence? The answer lies deep within human psychology and the history of scientific institutions. For centuries, humans have shown a remarkable capacity to believe in invisible forces shaping our lives – from ancient spirits to modern theories of contagion. When these beliefs become embedded in scientific institutions, they can persist for generations without proper scrutiny, protected by both psychological and social forces that resist questioning fundamental assumptions. Our tendency to accept invisible, untestable entities as explanations for observable phenomena reveals a pattern of thinking that spans cultures and epochs, one that continues to influence how we interpret disease and healing today.

This is not just a story about COVID-19. It is a deeper examination of how human beings think about disease, how scientific institutions maintain unproven theories, and why challenging these deeply held beliefs proves so difficult. As we will see, the entire field of virology rests on foundations far shakier than most realize, sustained more by human psychology than scientific evidence.

What follows is an investigation into both the technical failures of virology and the psychological factors that keep these failures hidden in plain sight. It is an exploration of how human beings can collectively maintain beliefs that, when examined carefully, lack solid scientific foundation. Most importantly, it is a call to reexamine what we think we know about disease, contagion, and the invisible world we cannot see.

PART 2 – THE TECHNICAL FAILURE OF VIROLOGY: A HISTORY OF FLAWED METHODS

When examining the foundations of virology, we must start with a simple but crucial question: How does a virologist prove the existence of a new virus? The answer reveals a field built not on direct evidence, but on layers of inference and assumption.

In the popular imagination, discovering a virus might work something like this: Scientists take samples from sick patients, look at them under powerful microscopes, and find identical viral particles causing disease. These particles would be abundant in sick people, absent in healthy ones, and could be isolated, purified, and proven to cause illness when introduced to healthy organisms.

This logical approach – what we might call proper scientific methodology – has never been successfully performed in the history of virology. Not once. Not for any virus. This extraordinary claim requires extraordinary evidence, so let’s examine the actual methodology virologists use to claim the discovery of new viruses.

The Enders Legacy: How Uncontrolled Experiments Became Standard Practice

In 1954, John Franklin Enders published a paper that would fundamentally shape the field of virology. Attempting to study measles, Enders introduced an unpurified sample from patients exhibiting symptoms of illness into a mixture of cells and other biological material. When the cells showed signs of damage – what virologists call a “cytopathic effect” (CPE) – Enders concluded he had found evidence of a virus.

To understand the significance of CPE, we must first understand what it actually represents. The cytopathic effect refers to visible changes that occur when cells die or become damaged in laboratory cultures. These changes include cells becoming enlarged, misshapen, or developing holes (called vacuoles) in their structure. Virologists interpret these cellular changes as evidence of viral infection – but this interpretation relies on a crucial assumption that has never been properly proven through controlled experiments.

Consider this analogy: If you added a potentially toxic substance to a fish tank and the fish died, you wouldn’t automatically conclude that a virus killed them. You would first need to rule out other potential causes of death, including the toxic substance itself. Yet this basic scientific principle – the use of proper controls – has been largely ignored in virology.

PART 3 – THE FATALLY FLAWED FOUNDATION

The methodological failures of Enders cast a long shadow over modern virology. His work suffered from a fundamental flaw that any first-year science student should recognize: the absence of proper control experiments. Without these controls, there was no way to determine whether the cellular damage he observed came from a virus or from his experimental method itself. Even more telling, Enders himself acknowledged this critical problem, noting that “similar cytopathic changes have been observed by others in uninoculated cultures of monkey kidney tissue.” This admission should have halted the field in its tracks. Instead, his flawed methodology became the template for all future viral research.

The implications of this methodological failure became starkly apparent during the COVID-19 crisis. In 2020, Leon Caly and colleagues published what would become one of the most influential papers claiming to isolate SARS-CoV-2. Their work, conducted at the Doherty Institute in Melbourne, was heralded worldwide as proving the existence of the new coronavirus. Yet when we examine their methodology closely, we find the same fundamental errors that plagued Enders’ work decades earlier.

The Australian team began with an unpurified sample from a patient’s nasopharyngeal swab – a mixture containing countless proteins, genetic fragments, and cellular debris. This sample was introduced to a culture of Vero cells – kidney cells from an African green monkey. These cells were then stressed through the addition of antibiotics and minimal nutrients, a process known to cause cellular breakdown. When the cells showed signs of damage – the same “cytopathic effect” that Enders had observed – the researchers claimed this as evidence of viral infection.

Perhaps most revealing was their manipulation of the sample to create the appearance of the now-famous coronavirus “spike proteins.” Unable to find these characteristic features naturally, the researchers added the enzyme trypsin to their culture. This protein-digesting enzyme modified the appearance of particles in their sample, creating the crown-like projections that gave coronaviruses their name. In essence, they manufactured the very features they claimed to discover.

The parallels with Enders’ work extend to what was not done. No viral particles were ever purified from the patient sample. No demonstration was made that such particles, if they existed, could cause disease. Most critically, no proper control experiments were performed using other human samples to rule out alternative explanations for their observations. The researchers never proved that their observed particles weren’t simply the natural debris from dying cells – a possibility that becomes more likely given the harsh conditions of their experimental method.

This absence of controls represents more than just a technical oversight. It reveals a field so committed to finding viruses that it has abandoned the basic principles of scientific investigation. When we consider that this paper became a cornerstone of the global response to COVID-19, the implications become staggering. Policies affecting billions of lives were built upon evidence that wouldn’t pass basic scrutiny in any other field of science.

PART 4 – THE GENOME ILLUSION: CREATING VIRUSES IN SILICON

The creation of the SARS-CoV-2 genome represents perhaps the most extraordinary sleight of hand in modern scientific history. What most people imagine – and indeed what most doctors and scientists believe – is that virologists somehow extracted viral particles from sick patients, purified these particles, and then determined their genetic sequence. The reality proves far different, revealing a process built entirely on computer algorithms and circular reasoning.

The story begins with Fan Wu and colleagues in Wuhan, who published one of the first SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences. Their methodology reveals the fundamental problem with modern viral genomics. Starting with unpurified material from a patient’s lung washing, they performed what’s called metagenomic sequencing – a process that captures all genetic material present in a sample, whether human, bacterial, fungal, or potentially viral in origin. This created millions of short genetic fragments, none of which could be definitively attributed to any particular source.

To make sense of this genetic soup, the researchers turned to computer programs called Megahit and Trinity. These algorithms attempt to assemble complete genomes by comparing the fragments to existing databases of genetic sequences. It’s crucial to understand that these programs don’t discover or verify the existence of viruses – they merely create theoretical models based on pre-existing assumptions about what viral genomes shouldlook like.

The circular nature of this reasoning becomes clear when we examine how these reference databases were created. The existing “viral” sequences used for comparison were themselves generated through the same flawed process – none were ever proven to come from actual pathogenic particles. It’s a case of using theoretical models to create more theoretical models, with no connection to physical reality required.

This computer-generated nature of the SARS-CoV-2 genome explains one of the pandemic’s most puzzling features: the constant emergence of new “variants.” Each time researchers ran their samples through these genome assembly programs, they would get slightly different results. These variations weren’t evidence of a mutating virus but rather artifacts of the computational process itself. Every slightly different computer assembly was labeled a new “variant,” leading to an ever-expanding universe of theoretical genetic sequences, none tied to any proven physical entity.

The implications of this genomic sleight of hand extend far beyond academic concern. These computer-generated sequences became the blueprint for PCR tests worldwide. Testing laboratories weren’t looking for a virus; they were looking for fragments of a theoretical genetic sequence that existed only in computer databases. When these tests began returning “positive” results, it created the illusion of viral spread – yet at no point was anyone detecting an actual virus.

This disconnect between computer models and physical reality represents a fundamental crisis in modern science. We have replaced direct observation and proper isolation with computer simulations and algorithmic assumptions. The result is a kind of virtual virology, where digital constructs are treated as physical entities, and computer modeling replaces scientific proof.

PART 5 – THE PSYCHOLOGY OF SCIENTIFIC BELIEF: PATTERN RECOGNITION AND PARADIGM BLINDNESS

When presented with the methodological failures of virology, many ask how an entire field of science could be so fundamentally flawed. The question itself reveals our tendency to assume that widespread belief correlates with truth – a logical fallacy that has persisted throughout scientific history. The answer lies in understanding how human psychology shapes our interpretation of evidence, particularly when dealing with invisible phenomena and complex systems of disease.

The story of Ignaz Semmelweis provides a perfect illustration of how our psychological predispositions shape scientific interpretation. In 1847, Semmelweis observed that when doctors washed their hands between performing autopsies and delivering babies, maternal mortality rates dropped dramatically. This observation has been enshrined in medical history as proof of germ theory – doctors, the story goes, were spreading deadly bacteria from corpses to mothers.

Yet this interpretation reveals more about our psychological need for simple, agent-based explanations than it does about scientific reality. Consider what Semmelweis actually observed: women died less frequently when doctors washed their hands after handling corpses. From this observation, generations of scientists and doctors have concluded that bacteria must have been the killer. However, these doctors were handling bodies preserved with toxic chemicals like formaldehyde. They were exposed to various decomposition products, unknown chemical compounds, and other potentially harmful substances. The assumption that bacteria caused the deaths, rather than chemical contamination or other factors, reveals our tendency to see what we expect to see.

The Power of Pattern Recognition and Historical Misinterpretation

The historical record provides numerous examples of how our pattern-recognition bias leads to false conclusions about disease transmission. Consider how sailors on long voyages would fall ill with scurvy, one after another. Medical authorities of the time were convinced they were witnessing contagion. The pattern seemed clear: one sailor would get sick, then another, then another. Yet we now know scurvy results from vitamin C deficiency – something all sailors shared due to their limited diet. The pattern was real, but the interpretation was wrong.

This same misinterpretation occurred repeatedly throughout medical history. Pellagra and beriberi, both ultimately shown to be B vitamin deficiencies, were initially thought to be contagious diseases. In each case, scientists were convinced they were witnessing infection spread from person to person. The pattern-recognition machinery of their minds created a story of contagion where none existed.

This tendency persists in our modern understanding of illness. When multiple people in a household fall ill around the same time, it seems natural to conclude that something passed between them. This apparent pattern of contagion is so compelling that we rarely consider alternative explanations – shared environmental exposures, similar susceptibilities, or common stress factors affecting the household. Our pattern-recognition machinery kicks in, and we “see” contagion, even though we’ve never observed any virus passing between people.

The Invisible Enemy: From Ancient Spirits to Modern Viruses

Perhaps most revealing is humanity’s persistent tendency to believe in invisible entities that can possess or influence the body. From ancient beliefs in spirits to modern theories of viral infection, we see a remarkable consistency in how humans conceptualize invisible forces affecting health. This psychological predisposition helps explain why virus theory found such ready acceptance – it fits perfectly into pre-existing mental frameworks about invisible entities that can invade and possess us.

The language of viral infection often mirrors ancient descriptions of spirit possession: the virus “enters” the body, “takes over” cells, and “spreads” to others. This parallel is no coincidence. The virus theory essentially functions as a modern version of demon possession, where we’ve simply replaced supernatural entities with biological ones, while maintaining the same underlying psychological pattern of invasion and possession. This replacement of spirits with viruses reveals how deeply rooted our tendency is to explain illness through invisible, invading entities.

This tendency becomes particularly problematic when combined with our modern technological capacity to generate vast amounts of data. Computer modeling and genetic sequencing create patterns that seem meaningful but may reflect nothing more than our own programmed expectations. When we “find” viral sequences using programs designed to look for viral sequences, we’re often seeing nothing more than the reflection of our own assumptions.

Confirmation Bias: The Self-Reinforcing Nature of Viral Theory

The power of these psychological predispositions becomes most evident when we examine how virologists interpret their experiments. Confirmation bias – the tendency to interpret evidence as confirming our existing beliefs – shapes every aspect of virological research. This bias transforms even contradictory evidence into supposed proof of viral existence.

Consider how virologists interpret the death of cells in their cultures. When they observe what they call cytopathic effects (CPE) – the breakdown and death of cells in their test tubes – they immediately attribute this to viral infection. This interpretation persists even though they lack the proper control experiments to rule out other causes, such as the toxic conditions of their experimental methods themselves. The circular reasoning is remarkable: they believe viruses exist, they believe viruses kill cells, therefore when cells die, it must be because of viruses.

This confirmation bias reached new heights during the SARS-CoV-2 research. As detailed by Dr. Mark Bailey, when researchers found they needed to add the enzyme trypsin to create the appearance of spike proteins on their supposed viral particles, they didn’t question whether they were manufacturing artificial structures. Instead, they simply accepted this manipulation as part of their methodology. Rather than seeing this need for artificial manipulation as evidence against their viral theory, they interpreted it as further confirmation of what they already believed.

The same bias appears in genetic research. When virologists find genetic fragments in sick patients, they immediately assume these must come from viruses – despite never having proven that such fragments originate from pathogenic particles. They design computer programs to look for viral sequences, and when these programs find what they’re designed to find, they accept this as proof of viral existence. It’s akin to creating a computer program to find evidence of dragons, then claiming the program’s output proves dragons exist.

This confirmation bias creates a self-reinforcing system where every observation, no matter how contradictory to viral theory, gets interpreted as supporting it. Failed isolation attempts become “evidence” of how hard viruses are to isolate. The need to artificially create viral features becomes “proof” of viral adaptability. The inability to find complete viral genomes in any patient becomes explanation for why we need computer programs to “discover” them.

PART 6 – INSTITUTIONAL RESISTANCE: WHY PARADIGMS PERSIST

In his landmark work “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Thomas Kuhn demonstrated how scientific paradigms maintain themselves long after evidence has undermined their foundations. The case of virology provides a perfect illustration of Kuhn’s principles in action, showing how institutional forces work to prevent the questioning of fundamental assumptions.

Modern virology has evolved far beyond a mere scientific field into a vast industrial complex that interweaves pharmaceutical companies, research institutions, government agencies, and countless academic careers. The economic implications of acknowledging virology’s foundational flaws would shake the foundations of multiple industries and institutions. Billions of dollars invested in vaccine development would be called into question. Entire careers built on viral research would crumble. Government agencies dedicated to viral surveillance would lose their reason for existence. The medical testing industry, heavily dependent on viral diagnostics, would face a crisis of purpose.

The institutional resistance to questioning viral theory extends far beyond the defense of scientific ideas. At stake are countless livelihoods, professional reputations, and entire economic systems built around the viral paradigm. Research grants, academic positions, pharmaceutical profits, and public health bureaucracies all depend on maintaining the virus narrative. This financial and institutional entrenchment cuts to the heart of why paradigm shifts face such fierce resistance. The stakes extend far beyond scientific truth; they touch the very foundations of modern medical economics and institutional power.

The Gatekeepers of Knowledge

The mechanisms of modern censorship operate with subtle sophistication, far removed from the obvious suppression of ideas seen in previous eras. Within academic institutions, a complex web of gatekeeping maintains the viral paradigm. Journal editors quietly reject papers that question viral theory, not through outright censorship, but through the peer review process that ensures conformity to accepted beliefs. Grant committees, holding the purse strings of research funding, effectively control the direction of scientific inquiry by supporting only those projects that align with established viral theory. The tenure system itself becomes a powerful tool for maintaining the paradigm, as young scientists quickly learn that career advancement depends on adherence to accepted views.

The COVID-19 crisis revealed an even more insidious form of control through the emergence of institutional “fact-checking.” Under the guise of protecting public health, social media platforms, news organizations, and scientific journals implemented unprecedented restrictions on discourse about viral theory. As Dr. Bailey documents, even highly credentialed scientists found their work labeled as “misinformation” if it challenged the dominant narrative. This system of information control effectively created a new form of censorship, one that operates not through direct suppression but through the manipulation of what information is considered acceptable for public consumption.

Scientists who dare to question viral theory face severe professional consequences. The message reverberates clearly through academic halls: challenge the paradigm, and you risk everything – funding, reputation, career advancement. This silent threat ensures compliance more effectively than any direct censorship could achieve. The result is a self-perpetuating system where questioning fundamental assumptions becomes professionally dangerous, ensuring that the viral paradigm remains protected from serious scientific scrutiny.

PART 7 – ALTERNATIVE PARADIGMS: A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF DISEASE

The collapse of the viral theory opens the door to more nuanced and scientifically rigorous understandings of health and illness. Among these alternative paradigms, German New Medicine (GNM), developed by Dr. Ryke Geerd Hamer, offers perhaps the most revolutionary perspective on disease and healing.

Hamer’s discoveries fundamentally challenge our conception of disease. Where conventional medicine sees sickness as something to fight, GNM recognizes biological processes as meaningful responses serving specific purposes. This understanding inverts the conventional paradigm: what we typically consider symptoms of illness emerge as signs of healing, biological programs with precise purposes and predictable patterns.

At the heart of German New Medicine lies a profound understanding of how biological conflicts shape disease processes. Every disease, Hamer discovered, begins with an unexpected shock or trauma that catches us off guard. This initial conflict sets in motion a two-phase response: first, a conflict-active phase where the body adapts to the shock, followed by a healing phase when the conflict finds resolution. These phases correlate with specific brain areas, demonstrating the intimate connection between our nervous system and disease processes.

Perhaps most revolutionary is Hamer’s insight into the role of microbes. Rather than viewing them as hostile invaders, GNM recognizes them as supportive agents in the body’s healing processes. This understanding aligns with growing evidence that many microorganisms serve beneficial rather than pathogenic roles in human biology.

This framework explains phenomena that viral theory struggles to address. Consider why people often experience cold symptoms after resolving emotional conflicts. From the GNM perspective, these symptoms don’t represent an invasion of pathogens but rather the body’s healing response following conflict resolution. The timing of symptoms, their progression, and their resolution all follow predictable patterns tied to the resolution of biological conflicts.

Complementary Understanding: The Environmental Perspective

Beyond German New Medicine, our understanding of health deepens further when we consider the crucial role of environmental factors in disease. The historical record reveals numerous instances where supposed “epidemics” stemmed not from contagion but from environmental causes. As Dr. Cowan demonstrates, conditions once attributed to infectious spread – from scurvy on sailing vessels to pellagra in the American South – ultimately proved to be responses to environmental factors such as nutritional deficiencies, toxic exposures, and poor air quality.

The role of water in biological systems offers particularly compelling insights into health and disease. Dr. Cowan’s research reveals that water, comprising roughly 70% of our bodies, serves as far more than a passive medium for biological processes. Instead, it functions as a sophisticated information carrier and structural element fundamental to cellular health. When we understand how environmental influences affect the structural integrity of our cellular water, we find more logical explanations for disease patterns than theories about invisible, never-isolated viral particles.

These modern insights find historical precedent in the work of pioneering scientists like Antoine Béchamp, whose research on pleomorphism and microzymas challenged the dominant germ theory of his time. Béchamp’s observations revealed microorganisms as adaptive entities responding to their environment rather than hostile invaders. His work demonstrated that changes in cellular terrain determine microbial behavior, not the other way around – a finding that aligns remarkably well with current understanding of the microbiome and cellular biology.

The synthesis of these various perspectives – from German New Medicine’s biological conflicts to environmental influences and water’s structural role – provides a more complete and scientifically sound framework for understanding health and disease. This framework doesn’t require belief in unproven viral particles or unexplained mechanisms of contagion. Instead, it rests on observable phenomena and logical relationships between biological systems and their environment.

PART 8 – MOVING FORWARD WITH HUMILITY

The collapse of virology as a scientific paradigm presents both a challenge and an opportunity. While we must acknowledge the failure of viral theory, we should resist the temptation to simply replace it with another all-encompassing explanation for disease. Perhaps the most profound lesson we can learn from virology’s failure is the importance of intellectual humility when confronting the mysteries of health and disease.

What we can say with certainty is that the body possesses remarkable capacities for healing and self-regulation that we are only beginning to understand. When we observe a fever, we needn’t construct elaborate theories about viral invasions to appreciate its purpose. We can simply acknowledge it as one of many intelligent processes our bodies employ in maintaining health. The same applies to inflammation, discharge, and other symptoms we’ve been taught to fear and suppress.

This perspective doesn’t require us to fully understand every biological process or accept any particular theory of disease. Instead, it invites us to approach health with wonder and respect for the body’s inherent wisdom. Some aspects of healing may remain forever beyond our complete understanding – and that’s okay. We don’t need to explain everything to work effectively with our bodies’ natural tendencies toward health.

The environmental factors affecting our health – air quality, water purity, nutrition, electromagnetic influences – deserve our attention precisely because we can observe and measure their effects directly, without requiring belief in invisible, unproven entities. Yet even here, we must maintain humility about the complexity of these relationships and resist oversimplified explanations.

This approach transforms public health from a war against invisible enemies into a more grounded effort to support human health through observable, practical measures. Rather than claiming to understand everything about disease, we can focus on creating conditions that support health while remaining open to new discoveries and perspectives.

Ultimately, this reorientation suggests that true health comes not from believing in any particular theory but from respecting the profound complexity of living systems while working with, rather than against, our bodies’ natural processes. Some mysteries of health and healing may remain forever beyond our grasp – and recognizing this limitation might be the first step toward genuine wisdom in medicine.

CONCLUSION: THE COURAGE TO QUESTION AND EMBRACE UNCERTAINTY

The story of virology represents more than just a scientific error – it embodies humanity’s complex relationship with uncertainty, our desire for simple explanations, and our tendency to build institutional power around comforting but unproven beliefs. As we’ve seen, virology’s failure to meet basic scientific standards has been overshadowed by our psychological need to explain the mysterious and our institutional resistance to acknowledging fundamental errors.

The implications of this understanding stretch far beyond academic debate. The COVID-19 crisis demonstrated how unproven theories can reshape society when wielded by institutional power. Measures like lockdowns, masks, and mass vaccination programs were all predicated on the existence of a pathogenic virus that has never been properly isolated or proven to cause disease – a sobering reminder of how theoretical constructs can have profound real-world consequences.

Yet this critical analysis isn’t merely deconstructive. By understanding how psychological factors and institutional forces maintain unproven theories, we open ourselves to a more humble approach to health and disease. While various alternative perspectives offer valuable insights, we need not replace one dogma with another. Perhaps the most valuable lesson from virology’s collapse is the importance of acknowledging what we don’t know.

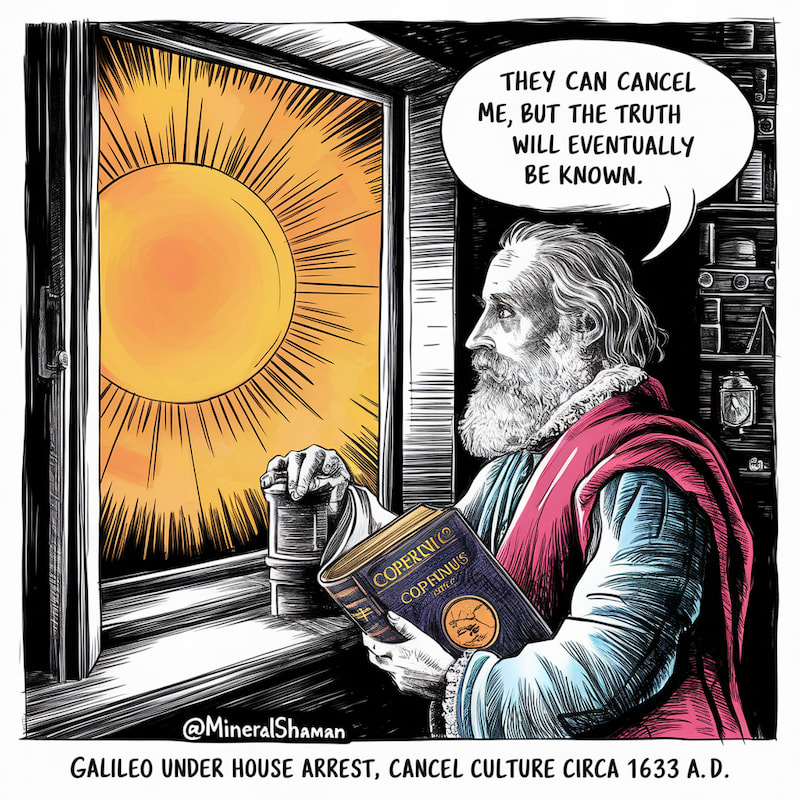

The path forward requires multiple forms of courage – courage to question deeply held beliefs, courage to face institutional opposition, and perhaps most importantly, courage to admit that some aspects of health and disease may lie beyond our complete understanding. Just as the Copernican revolution required humanity to abandon its presumed central position in the cosmos, moving beyond the viral paradigm requires us to abandon our presumption of complete knowledge over biological processes.

This transformation won’t be easy. As Thomas Kuhn observed, paradigm shifts often require generational change. Those most invested in current theories – both financially and psychologically – are least likely to question them. Real change typically comes from those willing to look at evidence with fresh eyes and, crucially, those willing to admit the limitations of human knowledge.

For those ready to question viral theory, the journey begins not with accepting new beliefs but with examining the evidence, or rather the lack thereof, for what we’ve been taught to believe. It continues with openness to observable phenomena while maintaining healthy skepticism toward all-encompassing explanations. And it leads, ultimately, to a more humble understanding of health – one that recognizes our body’s innate wisdom without claiming to fully understand it.

The future of medicine lies not in fighting imagined viral particles, nor in creating new theoretical frameworks to replace old ones. Instead, it lies in supporting the body’s natural processes while acknowledging the profound mystery of life itself. It means accepting that symptoms might serve purposes we don’t fully understand, that environmental factors influence health in complex ways, and that true science requires both careful observation and intellectual humility.

As we bid farewell to virology, we step not into a new paradigm but into a space of greater uncertainty – one where observable evidence guides us while mystery surrounds us. The question is not whether this transition will occur, but whether we have the courage to embrace both the knowledge we can gain and the uncertainty that remains.

REFERENCES

Primary Sources

Bailey, M. (2022). A Farewell to Virology (Expert Edition). Retrieved from drsambailey.com/a-farewell-to-virology-expert-edition/

Caly, L., Druce, J., Roberts, J., et al. (2020). Isolation and rapid sharing of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) from the first patient diagnosed with COVID-19 in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 212(10), 459-462.

Cowan, T. (2021). Breaking the Spell: The Scientific Evidence for Ending the COVID Delusion. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Enders, J.F., & Peebles, T.C. (1954). Propagation in tissue cultures of cytopathogenic agents from patients with measles. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 86(2), 277-286.

Fan Wu, et al. (2020). A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature, 579, 265-269.

Lanka, S. (2021). Preliminary results: Response of primary human epithelial cells to stringent virus amplification protocols (unpublished).

Secondary Sources

Historical and Foundational Works

Béchamp, A. (1912). The Blood and its Third Element. [Translation by Montague R. Leverson].

Bernard, C. (1865). An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine. [1957 translation, Henry Copley Greene].

Kuhn, T. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

German New Medicine and Alternative Paradigms

Hamer, R.G. (2000). Summary of the New Medicine. Amici di Dirk.

Cowan, T. (2019). Cancer and the New Biology of Water: Why the War on Cancer Has Failed and What That Means for More Effective Prevention and Treatment. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Water Research and Environmental Factors

Pollack, G.H. (2013). The Fourth Phase of Water: Beyond Solid, Liquid, and Vapor. Ebner & Sons.

Firstenberg, A. (2017). The Invisible Rainbow: A History of Electricity and Life. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Methodology and Critical Analysis

Engelbrecht, T., et al. (2021). Virus Mania: Corona/COVID-19, Measles, Swine Flu, Cervical Cancer, Avian Flu, SARS, BSE, Hepatitis C, AIDS, Polio, Spanish Flu. How the Medical Industry Continually Invents Epidemics, Making Billion-Dollar Profits at Our Expense. 3rd English Edition.

Freedom of Information Documents

Massey, C. (2020-2022). Collection of FOI Responses Regarding SARS-CoV-2 Isolation. Retrieved from fluoridefreepeel.ca

CDC Response (Ref: #21-01704-FOIA), March 29, 2022

UK Health Security Agency Response (Ref: FOI 21/22-516), October 27, 2021

Public Health Agency of Canada Response (Ref: A-2020-000208), June 24, 2020

Australian Department of Health Response (Ref: FOI 2309), September 15, 2020

New Zealand Ministry of Health Response (Ref: H202102878), August 12, 2021

Institutional and Protocol Documents

World Health Organization. (2021). Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: a guide to implementation for maximum impact on public health. January 8, 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel. Revision 6, December 1, 2020.